31-year-old Raukaiya is holding a tiny compact mirror up to her face. With shiny hair pulled back into a loose ponytail, she looks intently at her reflection, and fixedly wipes off a smudge of thick black eyeliner. Not content, she gets up and walks over to a bigger mirror which stretches from ceiling to floor. Here she looks more closely at her left eye, pulls out a string of sleep gunk and steps back. Again she considers her reflection, smiles and walks off.

To a bystander, it’s looks insignificant – you’d barely notice – but for Raukaiya, it’s an extremely powerful gesture.

In 2002, a man – her sister’s brother-in-law – chucked acid on her face. Aged 15, she had rejected his marriage proposal. The acid disfigured the left side of her face and neck. For years, she didn’t leave her house. She refused to drink water and hid in the kitchen when anyone came over.

So, 16 years later, to look in the mirror and smile? To actually like what she sees? That’s a truly remarkable change.

“I kept fighting,” she says. “I didn’t recognise myself anymore but then I found Sheroes.”

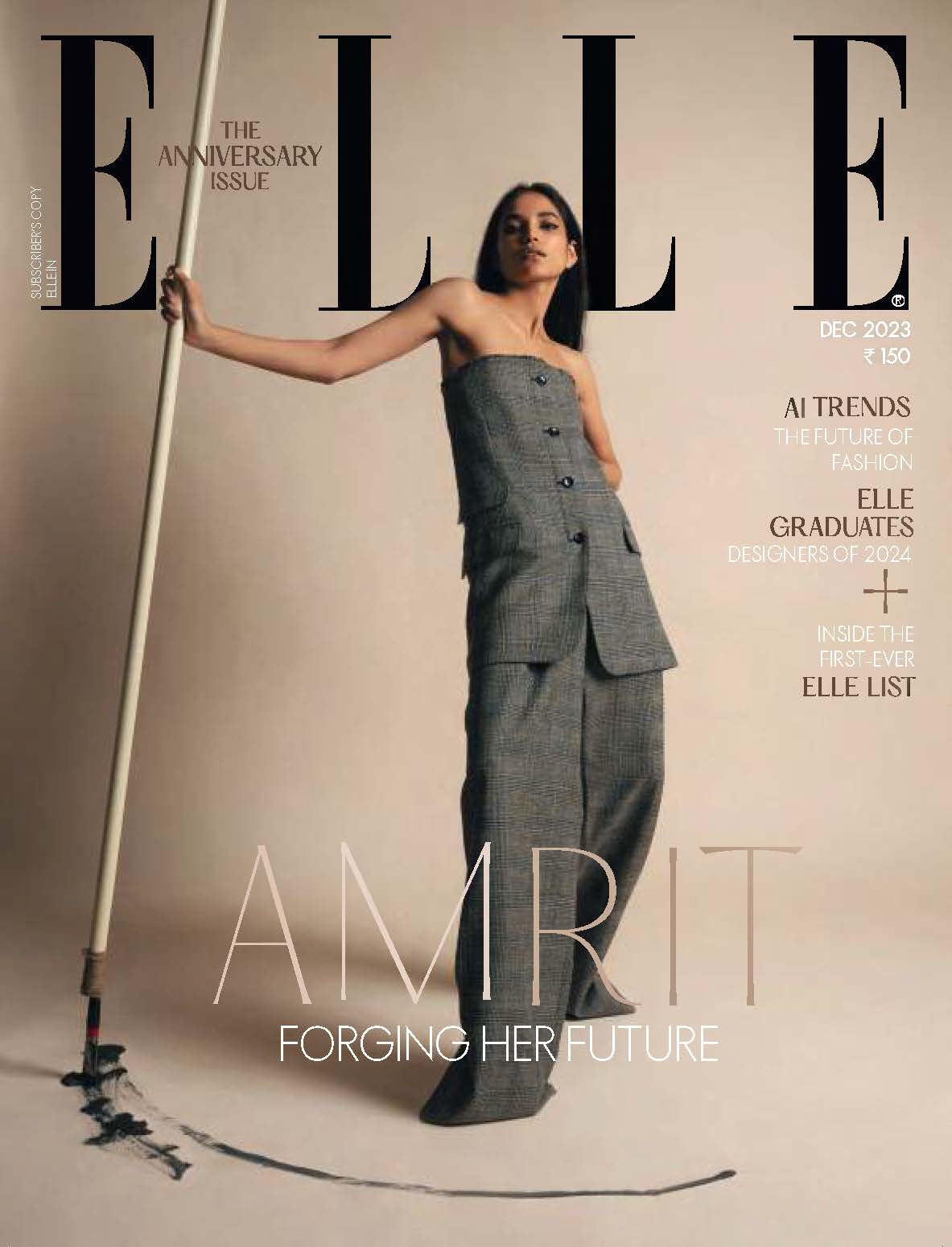

Photo: Smita Sharma

Close to the Taj Mahal in Agra, north India, is a café called Sheroes Hangout. Raukaiya is one of seven women who work as chefs or waitresses serving hot drinks and food.

But the female staff have one thing in common: they’ve all survived brutal acid attacks.

It’s lunchtime on a scorching hot day (the thermostat is pushing 42 degrees) and the four women on shift today sit round a table laughing and joking. Posters of female survivors line the café’s walls; each displays the face of a woman, her name, and the date she was attacked.

In one corner, t-shirts that read ‘Stop Acid Attacks’ and ‘My beauty is my smile’ are for sale. Founded in 2014 by Stop Acid Attacks, a New Delhi-based non-profit, Sheroes aims to create awareness of acid attacks and to boost confidence in survivors. The women receive counselling and are encouraged to talk about what happened with customers to reduce stigma.

When the café opened in 2014, most of the women hadn’t been out in public for years. If they did, they’d cover their faces. Not only did the acid melt Raukaiya’s skin – she had four facial reconstructive surgeries – it also destroyed her confidence.

“I had always dreamed of starting a boutique,” she explains. “I really enjoyed sewing. But after the attack I just stopped going out. I stopped speaking to everyone. So my dream stayed in my heart.”

Acid attacks are on the rise across India. In 2016, figures show 300 attacks were recorded (up from 249 the previous year) but the real number could exceed 1,000 per year, say human rights groups. Unsurprisingly, many incidences go unreported.

The majority of acid victims are women. They’re often attacked by male stalkers, jilted lovers, relatives or fathers. Whatever the reason, they’re usually premeditated and aimed at the face. The goal? Long-term damage.

“These people are so cruel,” explains 23-year-old Bala. On 12 May, 2012, she was attacked by her parents’ employer after a dispute. “A woman’s face is the most essential aspect of her beauty – they think the girl will sit at home and no one will marry her.”

When Bala first came to Sheroes she was ‘very shy’ – to date, she’s had seven facial surgeries – but things are different now. She’s since learnt to read and write and has picked up English from the many tourists who visit the café. Not only that, she’s more comfortable in her own skin: “I realised what happened wasn’t my fault. And I don’t cover my face as I walk anymore.”

In 2013, the country’s laws were reformed so that attacking someone with chemicals became punishable by up to 10 years in prison. But Bala doesn’t think the law is enforced well enough.

“Some victims’ cases are not even registered. If they are, these men appeal and get released on bail – what kind of message does that send?”

If a woman is attacked by a relative, there is often pressure to stay quiet and keep the issue within the family.

“Some people are scared and I understand,” says Bala. “But I wasn’t. My entire village was against me but I fought and got my case registered.”

Photo: Smita Sharma

Despite her attacker being jailed for just seven days, she felt ‘some peace’ over the sentence.

“My life was destroyed but how am I ruined? I’m living a good life. I’ve forgotten what happened but he’ll remember it for a long time.”

Others aren’t so lucky. When Madhu was 17, a local boy asked for her hand in marriage. After she refused – she was already engaged – it turned nasty.

“He said to me: “Marry me or run away with me. Otherwise see what I’ll do to you”’.

One day the boy walked past Madhu carrying a Pepsi can in his hand.

“I thought he’ll come and talk to me but he didn’t. He just poured acid on me. I shouted and screamed, but the street was empty. I passed out and woke up in the hospital.”

When Madhu’s mother attempted to register the case she was threatened. The family was small – Madhu’s father had died – and there was little support, so they dropped the case.

Now 31, she says healthcare facilities are better at dealing with severe chemical burns. But hospitals still lack resources and many women don’t get seen on time. Bala, for example, once travelled from Agra to Delhi (a five hour drive) to be told no doctors were available that day.

The problem is two-fold, says Madhu. Firstly, acid is still ‘openly’ sold despite the government limiting over-the-counter sales in 2013. Secondly, she believes men’s attitude towards women is ingrained from childhood.

“Boys grow up used to getting what they want,” she says. “So as adults, they think: “I desire this woman and I’ll marry her”. Men think women are worthless – like they’re dirt of the bottom of your shoe. And that’s why these attacks happen.”

Despite many perpetrators going unpunished, the women in Sheroes aren’t angry.

“I’ve been given a new life,” says 28-year-old Shabnam, who was attacked aged 15 by an ex-employer. One month after she quit her job, he came to her house in the middle of night.

“Before I didn’t want to go on living but now I feel like I’ve got a new family.”

She continues: “I used to think ‘I’m the only one who walks around with this ugly face’ but when I came to Sheroes I saw [other] people’s bravery. Why did I waste seven years of my life staying inside? Now I earn a salary and people listen to me. Customers ask “what happened to you?” and I tell them.”

The women are getting something more powerful than revenge: independence.

Photo: Smita Sharma

Despite being educated, the stigma attached to an acid attack survivor means many survivors can’t find jobs. A man once told Madhu that if her skin had been darker he would have employed her as a receptionist – her burns were too obvious. Earning a salary from working in the café, then, is life-changing for these women.

For years, Raukaiya lay awake at night thinking about the ways she could punish her attacker. She didn’t report the crime, so her sister’s brother-in-law walked free. With the help of Sheroes, however, it’s not that it doesn’t bother her anymore, more that her focus has shifted.

“I’ve forgotten what happened to me in the past. All I think about is what I have to do next, which is to educate my son and make him understand that he should respect women.”

Besides, asks Shabnam, what can’t women do?

“We have jobs, we drive rickshaws – girls are even flying helicopters. I’ll say this: if you haven’t left your home because you’ve been attacked, go out of your house. Do it now. Even when girls get pimples on their faces, they hide. Why? Our face isn’t beautiful, our heart is beautiful. Make yourself powerful, and fly high.”

Translation by Nikita Mandhani. Additional reporting by Smita Sharma.

From: ELLE UK