Regardless of a country’s stand on religion and secularism — in both scenarios, why is a woman’s choice of the garment always politicised? The opinion that a piece of clothing is oppressive or not should be with the women wearing it. Not the men in her life, not her community and definitely not the government in power.

On 16 September 2022, a 22-year-old Iranian woman named Mahsa Amini died in Iran due to police brutality for her non-compliance with the country’s hijab regulations. According to the Eyewitnesses, she was beaten and her head hit the side of a police car, which led to a cerebral haemorrhage and stroke. Laws that force women to cover or uncover their bodies are hardly democratic but heavily. draconian.

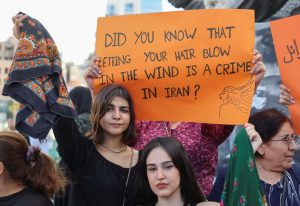

Women of Iran have taken to the streets to protest her death—marching with slogans like, ‘death to the dictator’. With 10 million retweets, the hashtag #MahsaAmini became one of the most repeated hashtags on Persian Twitter. In solidarity against this regressive regime, many women are burning their hijabs and cutting off their hair in dissent.

Until a few years ago, women in middle eastern countries like Iraq, Saudi Arabia could be arrested for not covering their heads. In Iran and the Indonesian province of Aceh, it is still mandatory. This radicalization has forced women, both Muslim and non-Muslim, to wear a hijab under this oppressive law. Today, a young woman had to lose her life for the world to sit up and take notice of this fanaticism. From France to India to Iran, women are fighting the same battle—their right to choose

Last year, the hashtag #HandsOffMyHijab went viral after the French senate under the administration of President Emanuel Macron voted to ban children under the age of 18 and mothers who accompanied them on school trips from wearing the hijab and burkinis at swimming pools. Global voices like American Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad and Congresswoman Ilhan Omar condemned the action. Not only is this discriminatory in nature towards one religion (while 18 other religions can continue to cover their heads in different attires), but it also isolates Muslim women from practising their beliefs.

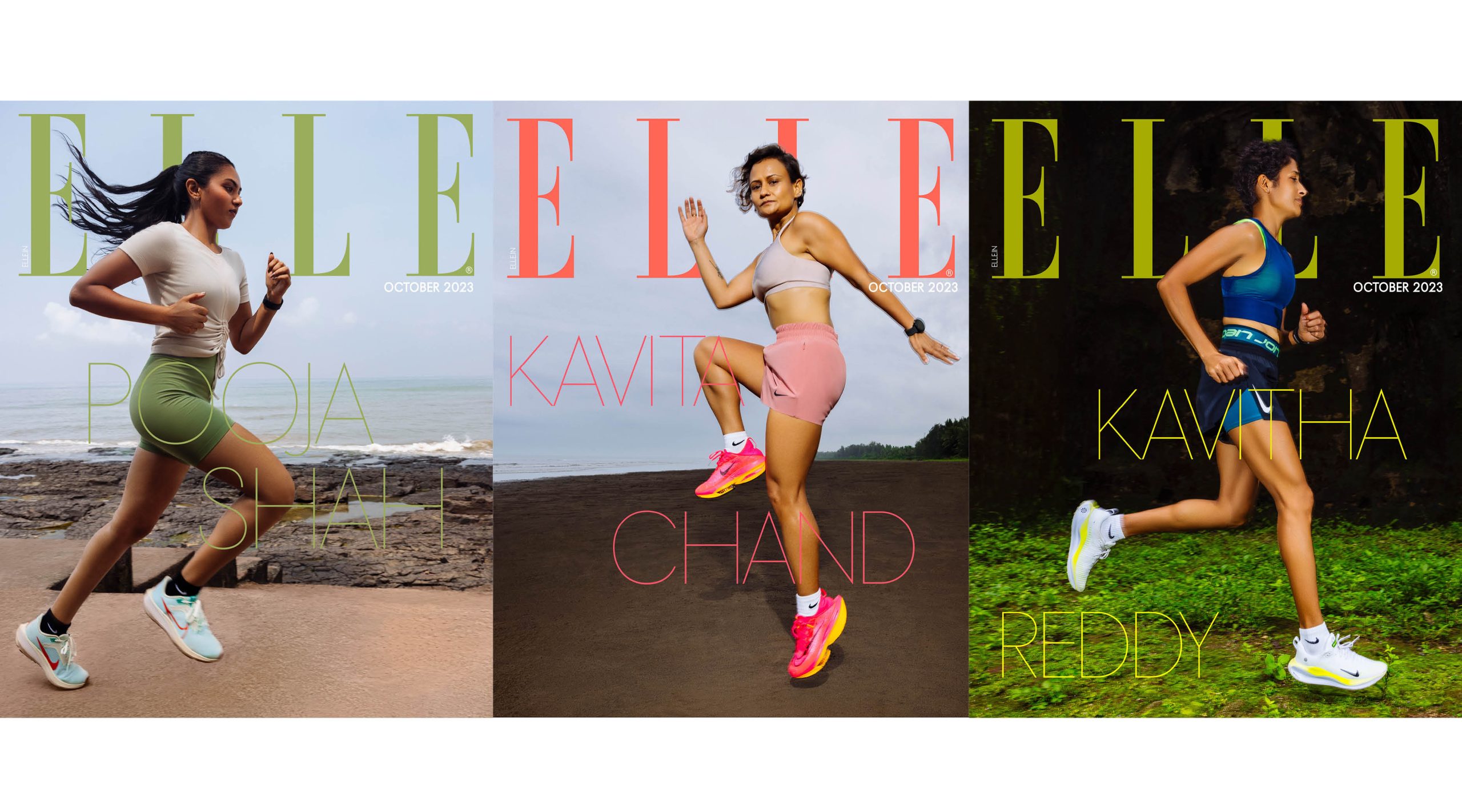

Just when the mainstream world of fashion, sports and arts had started acknowledging women for their individuality and making space for them by promoting modest campaigns and allowing them to participate in athletic competitions with headscarves, this regressive decision by countries like France, Norway and Switzerland undo their progress.

The narrative that clothes reflect culture is where the problem lies. The patriarchal policing on what’s appropriate and what’s not has existed since time immemorial. In Indian culture, a cropped top is shamed, while a sari is taken as a symbol of tradition. Ironically, both silhouettes are torso-baring, then what makes one more pious than the other? During the significant #MeToo movement, arguments about the length of a woman’s skirt being the cause for her sexual harassment have also been made while comparing her to a religious deity in the same sentence. They have been making, breaking and altering these rules according to their convenience as self-proclaimed protectors of female sanctity.

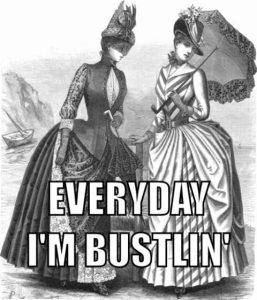

For instance, in the 1850s, during the first wave of feminism, middle-class women launched the Victorian dress reform movement (a.k.a the rational dress movement). Women wanted to adopt a more functional form of dressing instead of being suffocated and sexually objectified in tightly-laced corsets, crinolines (skirt lining) and bustles (bust pads). According to the reformists, this style of dressing was not only hazardous for their health but also the results of male conspiracy to make women more obedient by instilling this slave psychology in them.

The movement caught momentum and spread across the United States and multiple European countries, igniting the fire of change. The socio-political shift in women’s economic position in the 1920s further accelerated their say in what their closet should possess.

At the end of the day, none of these decisions about removing hijab or making it a compulsion addresses the actual issues women face. While we want the attention to be on matters like safety, gender pay gap, reproductive health and rights, access to education and menstrual stigma, the focus, unfortunately, continues to remain in the search of our misplaced morality.