Over the last few years, I’ve been thinking a lot about unanswerable questions. What happens when we die? How do we find happiness? (You know, the small stuff). So much so that I even wrote a book about my search for answers, called Stalking God: My Unorthodox Search For Something To Believe In (Seal Press), and did a TED talk about it. And I talk to pretty much everyone about these kinds of questions, pretty much every chance I get.So when I was asked to sit down with author Mira Jacob and chat about her attempts to answer the many questions her son asks her in her latest book, a graphic memoir titled Good Talk (Bloomsbury India), I was expecting to meet a kindred spirit. On a surface level, it is like we had lived parallel lives: first-generation South Asian American women, daughters of immigrants from India who were raised in a predominantly white American suburbs in the ’70s and ’80s, writers currently living in New York City, happily married for the better part of 20 years to childhood acquaintances, and one pre-tween aged child with a name starting with the letter Z. So I expected us to hit it off, and for her book to resonate with me, but our connection quickly went so much deeper than that.In reading Jacob’s book, you would forgive me for thinking she had been a fly on the wall to conversations (and my inner dialogue) throughout my entire life. And I found myself sending the following email to her as I turned the last page and wiped away tears:

“Dear Mira,Your book is extraordinary. I alternated between laughing and having a lump in my throat as I read it. I feel heartbroken and hopeful. I feel like we have lived parallel lives, and you have given voice to so many experiences and feelings that I’ve had over the years, many of which I’ve buried so deep that I couldn’t believe they were on the page in front of me. I thought you had eavesdropped into my life and experiences and I couldn’t figure out how you knew what I had been through.Thank you for writing this book. I consider it required reading for everyone in my life, especially if they want to understand the unique experience of growing up brown in America.”

One sunny spring afternoon, we had a chance to catch up in person in Tribeca over Greek coffee:

Anjali Kumar: When Zia was born, I realised one day she would ask me all sorts of existential questions that I didn’t have the answers to. And so, I went on a spiritual journey to try and figure out the answers. While your book is rooted in questions from your son too, I think the ones he asked you were even harder to answer. Tell me, how did the book come about?

Mira Jacob: It started because my son was obsessed with Michael Jackson and would ask me a thousand questions about him. I originally thought about doing it as an essay, but then I thought about the comments section that would accompany it (because that is what happens with essays…), and considering these were my son’s questions, it made me feel vulnerable. So, out of frustration, I drew us on printer paper and cut us out, and put our conversations in bubbles above us. And that became the first piece I did [for BuzzFeed, which went viral] and it felt really good, because suddenly, I wasn’t trying to convince a country of my racial pain. America is funny that way. It demands you talk about your racial pain so that a good portion of the population can tell you that it isn’t true and that they don’t believe you. And I didn’t want to get into that. When I did the cutouts, I felt like I wasn’t asking anyone for permission. My son and I were having a conversation. If you wanted to eavesdrop on us, you could go ahead, but I wasn’t begging you to care. That changed the equation dramatically—it gave me the headspace to be vulnerable, which was really hard to do after 2016 as we [the US] ramped up to becoming this place of complete intolerance. For the book, I decided to draw people as forward facing paper dolls. The only time I broke that rule was on the night of the election results, when I drew my son and I facing each other instead, with our foreheads touching. We were so sad. He was so bewildered; I didn’t know how to make sense of it for him. You get the idea that you know what it is like to be disillusioned with your country, and you realise you’ve just been in a lullaby.

AK: Yes, the backdrop of Trump’s victory in 2016 plays heavily into the narrative of the book. And it has had a deep impact on all of us living here, including South Asian Americans who have typically played into the “model minority” myth and kept our heads down for years.

MJ: Those of us, especially Indians who have bought into that myth and who benefit from the system, had many reasons to keep our heads down. But now, we are all implicated, and we have to ask ourselves: at whose expense was that? It’s a brutal question. Unpacking it has been really painful, and has also shown me the privilege I’ve had, to not have to feel this level of disillusion and attack by my government until now, unlike others, like black Americans and Mexican Americans, have felt from day one.

AK: Your in-laws, with whom you are close, are avid Trump supporters. What has that been like in these times?

MJ: My in-laws, who are Jewish, became avid Trump supporters. They love my son and they love me. And yet, they are incapable of connecting the dots between their vote and the world it will build for my son. There were a lot of white people I gave the benefit of the doubt, and then I realised it was wishful thinking on my part.

AK: Your book was optioned for television. I think it is potentially game changing for our kids to see their stories on American TV and to see these conversations advanced via that medium. Is that something you think about?

MJ: I can’t think about the impact that my art could make while I am making it or I won’t be able to say the hardest parts; I won’t be honest.I get 10 letters a day from people who are in mixed marriages, with usually the minority half of the couple saying, “Oh my God you see me. This is us too.” A lot of America has fantasies about interracial relationships, one of which is that you will all have beige babies who will save the world. But we know it just can’t be that simple. The converse reality is there is a lot of suspicion about interracial relationships—that the reason you are in one is because you must feel badly about yourself, that there must be some inequality in the relationship. Sure, it is hard to admit, but yes there is sometimes inequality in my marriage. Sometimes my husband gets me, and sometimes he overlooks me. We were raised in the same white patriarchy as everyone else, so we have the same issues in our marriage. Love did not conquer all of that. But to stand in that fiery place and still say, “Yes, there is love here, and it is real,” is deeply gratifying. That is what I got to do in this book, and I did it because no one else was doing it. It was really messing me up to not see anyone talking about what it was like to love someone across this brutal divide. There is a belief that love somehow makes racism impossible. And that is the biggest fantasy of all.

AK: What did you expect the book to be about when you first started writing it?

MJ: My son was six when I started writing. This was before the 2016 election. I thought it was going to be a hilarious collection of conversations. And then, as things got harder and harder, so many of the ones that were funny dropped out.

AK: What are some of your favourite conversations from the book?

MJ: With my son, I love the range of the Michael Jackson conversation, because it sets the tone for the rest of the book. And there is a great one with my dad, from when he was sick and I bought him pot. I love reading it and remembering what it was like to be in this territory with him that was at once both wild and new.

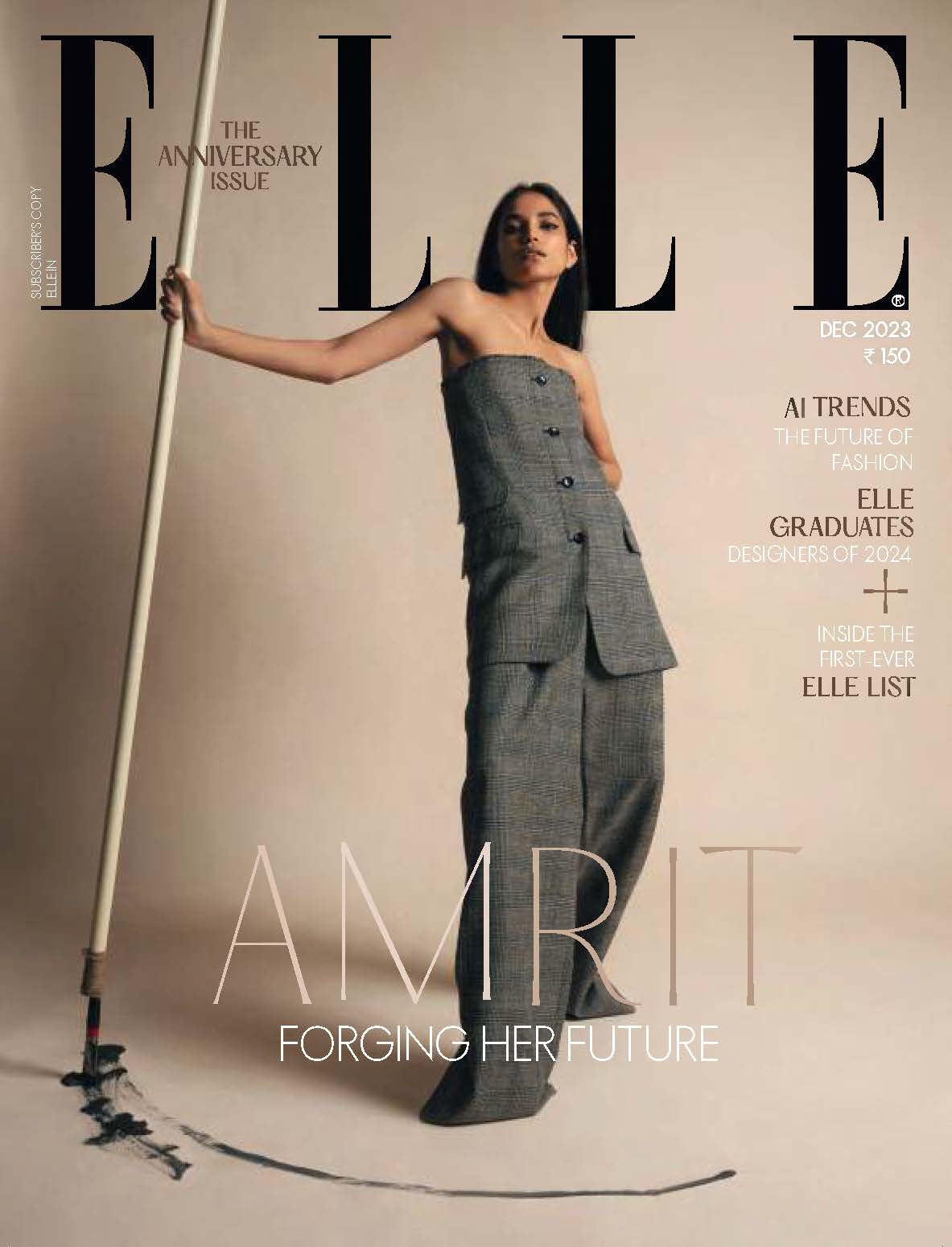

Mira Jacob; Photograph: In Kim

AK: What kind of America do you think your son and my daughter will grow up in? I am hoping you have an answer because I have no idea what to tell my child.

MJ: I currently live in Brooklyn, which is incredibly divided socially, economically and racially. There is the illusion of the mix, and there is the reality of it. This election has turned a very bright light on to all the beautiful lies we have told ourselves about how America works. My hope is that we are going to go through a big moment of national shame. It is something that Americans so loathe to do, and I think it is crippling us that we can’t even look back and hold ourselves accountable. My fear is that he will grow up and people will ask him what was it like to grow up in the country that was the United States of America.

Good Talk, published by Bloomsbury India, is now on stands