The book Indian Textiles: Past and Present by G. K. Ghosh and Shukla Ghosh offers an early record dating back over 300 years that described eri as “a silk, that is remarkably soft, white or yellowish, and the filaments so exceedingly delicate as to render it impracticable to wind off the silk.” The reason, the authors went on to write, is why the open-mouthed eri cocoon is spun like cotton, instead of being reeled like tassar or mulberry or muga cocoons. An alkaline solution made of specific plant ashes is heated and used to soften and degum the cocoon. This is then carefully opened by hand to extract the chrysalids, and the flattened cocoons are washed, kneaded, sun-dried, drawn into threads and spun into a fabric that is “finer than tassar silk but less fine than mulberry”.As for the moth itself? It emerges without disturbing the cocoon or its fibre, giving eri silk its other name – Ahimsa or peace silk. Yet, for all these properties, way back in 1903, the future of eri silk wasn’t considered favourable. In his classic book titled, A Monograph on the Silk Fabrics of Bengal, author N G Mukerji noted that “the eri silk industry is not so lucrative as the mulberry silk industry, the product of the eri cocoon being a spun-silk and not reeled silk. All attempts to reel the eri cocoon have hithero failed.”

Circa 2022, its future is still uncertain. Anupama Ambika Anilkumar, the Deputy Attaché for Scientific and University Cooperation, Institut français India, a section of the Embassy of France, reveals that eri silk comprises 21% of the total silk produced in India. “Yet, it is a small cottage industry, and all the advantages are unknown to a luxury market. Some of these include the fact that the handmade silk boasts chemical-free processing, is naturally dyed, sustainable, sturdy, breathable, ethical, easy to maintain, and versatile enough to work across a range of applications, from embroidery to crochet to shawls, bags, home linen or clothes. It is very unique, very special but certainly not cheap, and the need of the hour is to give the fabric and the people who work behind the scenes the support they deserve,” she says, explaining the decision to make this indigenous silk from the Northeast the highlight of the just concluded 2022 edition of the prestigious Silk In Lyon – Festival de la Soie.

As one of the largest trade and networking events for silks, this annual affair finds producers, entrepreneurs, design houses, designers, academicians, and researchers coming together on a single platform in the silk capital of France, Lyon. This year, unlike the last, when India was a guest of honour, she now held official representation, with Bangalore having cemented its official entry as a member of the Silk Cities Network. Savitha Suri, Textile Curator, Author, President of the WICCI Maharashtra Handloom Council and Director of Pravaaha Communications, who led the delegation at the festival, points out that while members of the India team dealt with different forms of silk as befitting not just the global platform but also the country, which holds the distinction of being the only one who produces all the major varieties of natural silk i.e., tasar, muga, eri and mulberry, within the delegation, the consensus was to highlight eri silk. “When we were there last year, we found a lot of concern around cruelty-free products. Luckily for us, we have an alternative already with us in India. We have a silk that checks all the boxes of the current requirements towards our environment, whether in terms of livelihood or sustainability. This is the time for India to step up and say, don’t look further than us because we already have it,” she says.

The need for this visibility is echoed by several designers and weavers. Eschewing the allure of the convenience of the power loom and the sway of fast fashion, weaver and owner of Gujarat-based Royal Brocades, Paresh Patel who works with handloom fabrics like Ashavali Brocades and natural eco-friendly dyes started experimenting with eri silk about a year ago only to find it superior to other fibres, right from its absorption of water to its conductivity. “In terms of appearance, the fact that it is subtly luxurious without being in-your-face shiny has massive appeal. The response has been good, especially in hot places like Gujarat where the weather is more conducive to wearing eri silk over mulberry. Given that it is an ethical option, I am considering shifting most of my production over to eri silk,” he says. But while Patel is a relatively new convert, Memorial Tmung, co-owner of Zong hi I, is a third-generation eri silk producer and weaver with a 15-year-old history with this fabric. She cites the thermal control of the fabric, which lends it properties of being warm in winter and cooling in summer as one of its biggest advantages, but laments its lack of representation in mainstream fashion. She puts this down to there being not enough knowledge about the silk and its texture. “When compared to other silks, eri has a rough-looking surface, more like wool or cotton, which makes it a very different texture from the lustre or sheen one normally expects a fabric like silk to have. Also, because production is done in very small quantities, in the village or cottage- type industry, the supply is often restricted to local needs.” Suri agrees about the appearance and says, “Apart from the fact that it’s not silky to the touch, and at first glance, could be mistaken for cotton to the uninformed eye, people don’t know where to access it from. It’s not like one can just walk on any road in the Northeast and pick up eri silk cocoons.

There is also limited production, which is hand woven, so it’s going to take time to spin. These are the limitations that need to be addressed, but it has the potential to be a game changer.” Jyoti Reddy, owner of Ereena, who has been working with eri silk weavers and artisans for over a decade, believes the opportunity to reduce the carbon footprint gives it a distinct advantage. The eri worm Philosamia Synthia Ricini (also called Samia Cynthia) feeds on the drought-resistant castor plant, which can subsist on rainwater or only 1 inch of water per week, while the mulberry silkworm, Bombyx Mori needs about 2 litres of water. Also, eri silk takes about 20% less water than other silks and definitely less than cotton. “Today, more than ever, the world of garments is concerned about supply chain transparency, carbon emissions and the search for sustainable fabrics. But, however beautiful and sustainable a raw material is, it has value only when it can be transformed into an appealing product,” says Reddy. “Eri silk is more utilitarian than one would imagine. We have a textile that is hand spun, hand woven, handcrafted, and a very adaptable fabric. We could actually market it as a high-end or luxury product. It’s about how we are going to make this fabric aspirational,” adds Suri. And that is exactly the kind of result the delegation hopes will come out of shining the spotlight on this fabric of peace that was once regarded as the ‘poor man’s silk’.

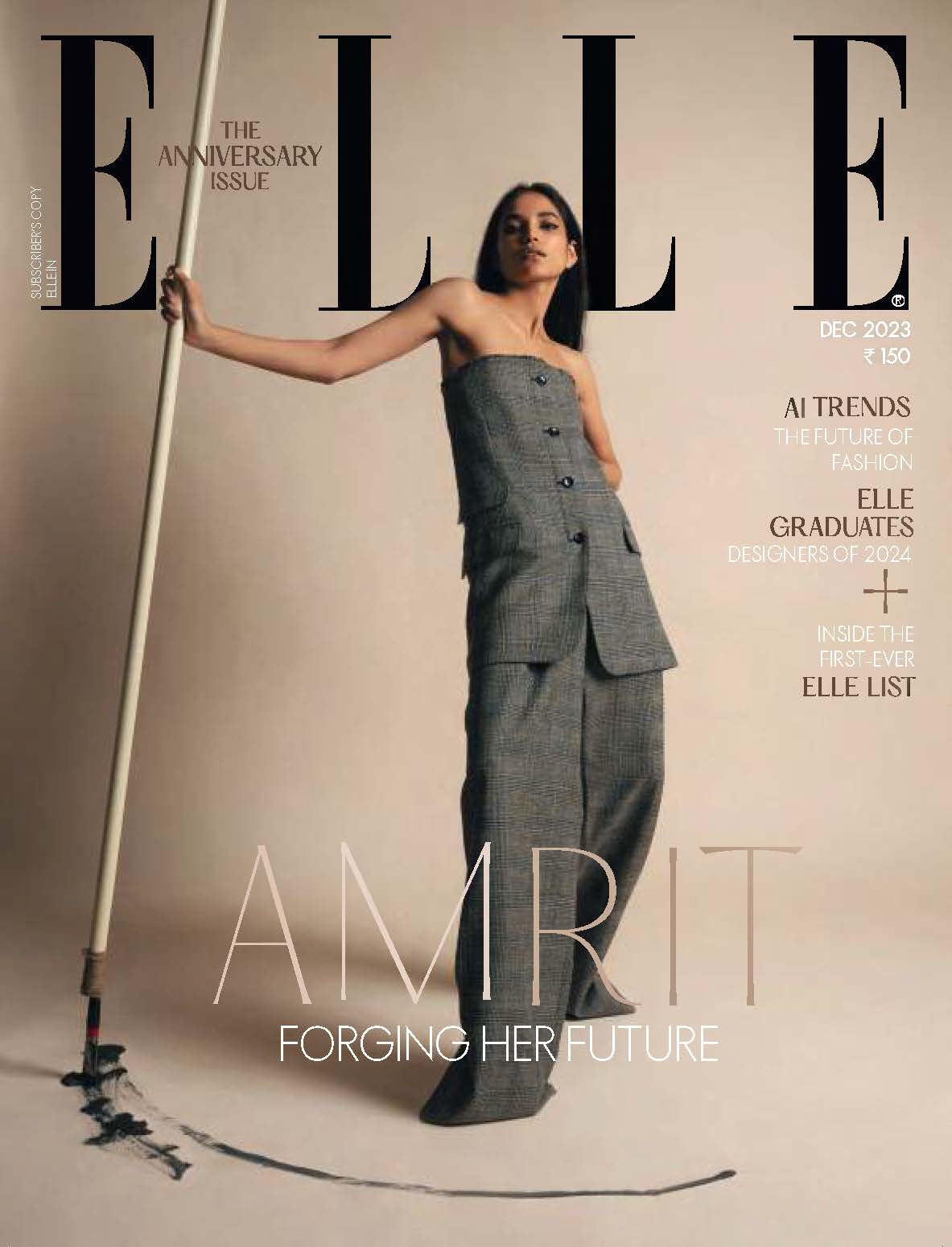

Find ELLE’s latest issue on stands or download your digital copy here.