It’s hard to believe that it’s been less than a month since Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced an end to all Covid restrictions in England. Wednesday night’s pot-banging in the street for the NHS has been swiftly replaced with a thumping bass after-work spin class. Sunday morning coffees on long walks have been trumped by hair of the dog at the pub. While we’re all relishing our newfound freedom after two years of pandemic stress, it seems we’re now on the cusp of another (albeit less severe) health crisis: competitive exhaustion.

Competitive exhaustion isn’t exactly a new phenomenon. But after the last two years it feels like it’s ramped up a notch. Now that we’re largely free to do as we wish, without the limitations of tiered lockdown restrictions and shuttered shop doors, the world seems on a mission to make up for lost time, filling every spare moment with frenzied social activity. And our bodies are simply ill-equipped.

Undoubtedly for most of us, hybrid working has resulted in a better work/life balance, but going to the office has never felt more laborious. Where before we might have jogged into town and maximised on the lunch hour with a trip to the post office as well as Pret, now simply the act of deciding what to wear in the morning is enough to drain all our brain power. The mental and physical toll of the pandemic rages on, while we attempt to go hard for the two years we’ve lost. The worst part? We’re turning our post-pandemic tiredness into a competition.

During a recent dinner with friends, no sooner than a bottle of Primitivo had been ordered, the conversation turned to our busy schedules. One friend took out her iPhone calendar and pointed at all the dots symbolising work functions, mini-breaks, and weddings over the next six months. Another arrived late from a post-work gym class, her tote bag bursting at the seams with laptop, knotted charging wires, a damp gym kit and a half-opened make-up bag – a visual representation of her hectic day. Feeling outdone on the tiredness spectrum, I began moaning about my greasy hair and dry skin – the result of another sleepless weekend of parties and boozy brunches.

To win the exhaustion war, I’ve learnt you need to pepper the conversation with talk of a recent argument with a loved one, a stomach bug, a self-imposed caffeine detox or sex-crazed foxes outside your bedroom window at 2am to stand a chance of finessing your bid.

We’re Turning Our Post-Pandemic Tiredness Into A Competition

Fatigue has achieved cult-like status in 2022, worn with pride like a box-fresh pair of Louis Vuitton knee-highs. We’re increasingly measuring our self-worth against how close to burn-out we are. If we’re not knocking back a third coffee by 11am or running between double-bookings, we’re not really living hard enough.

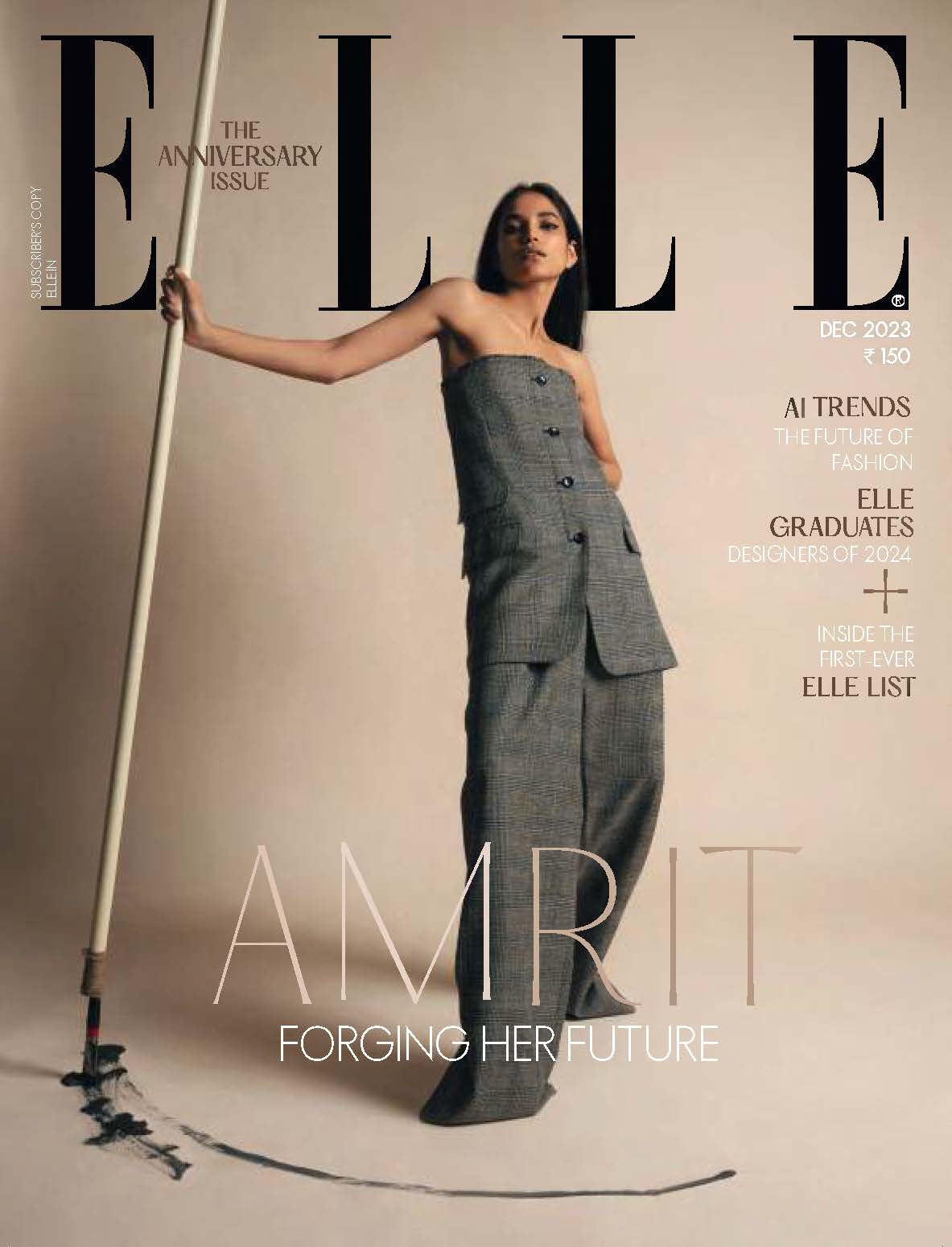

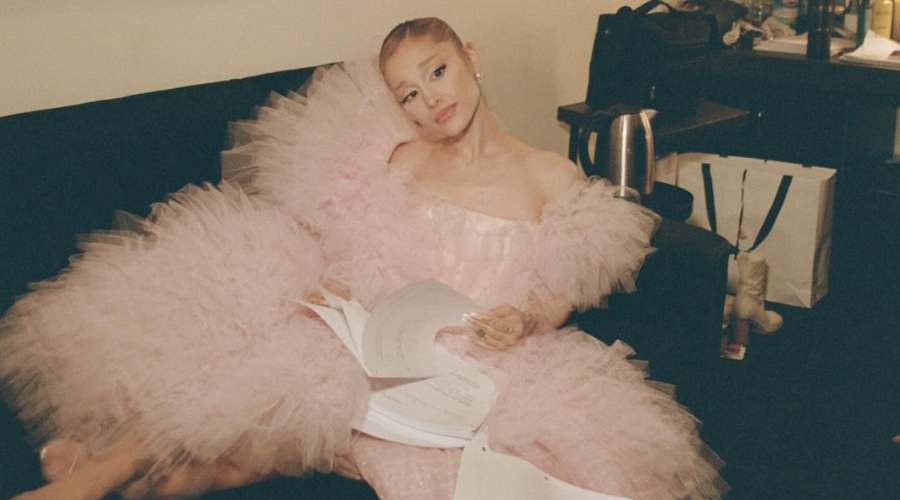

The popularity of exhaustion has even entered the beauty and fashion sphere. Models who walked SS22 shows at Altuzarra, David Koma and Balmain in February sported ‘greasy hair chic’, their slicked back wet hair signalling that it’s now universally acceptable to be too tired to bother drying your locks. Last year, under-eye circles became a viral TikTok beauty trend and involved applying layers of purple and blue eyeshadows under eyelashes to create the illusion of sleepless nights. The phenomenon came months after singer Grimes revealed that she purposefully enhances her own eyebags with red eyeshadow to appear ‘more demonic’. Where once people did everything to blur and soften signs of exhaustion, it’s now a beauty ideal to accentuate.

‘I’m shattered’ has become abbreviation for ‘I’m living to the max and I need you to know it’. And dinners are stacked with people that are one cocktail away from face-planting into their entrée.

Whereas Once People Hid Their Exhaustion, It’s Now A Beauty Ideal To Expose And Fight Over

And I’m tired of it. I’m tired of aggressive, competitive tiredness. Those of us not existing on just four hours of sleep are being made to feel like we’re failing at post-pandemic life. We’re not making up for lost time. Not helping everyone fast forward through the catching-up phase that might get us to where we could have been if two years of lockdown hadn’t got in the way.

Somewhere along the line we seem to have forgotten that exhaustion is a marker of illness, not success. It can result in headaches, depression, digestive problems, impaired memory and reckless risk-taking. It negatively impacts performance at work, family life, and social relationships. It’s also one of the key symptoms of long-Covid, with sufferers facing a daily battle to complete tasks which weren’t previously difficult. A friend, who caught Covid in 2021, informs me she can barely stay awake during the working day and has been forced to swap her 3pm pick-me-up coffee for an hour-long nap. Another says that a year after recovering from Covid she struggles with brain fog, which is having an adverse effect on her hopes for a job promotion. It seems insulting that the otherwise well would be competing for a symptom that these women would do anything to overcome.

An Eight-Hour Slumber, It Would Seem To Some, Is Now The Preserve Of Amateurs

If the pandemic has taught us anything, it should be the importance of looking after our health and taking stock of what matters most in life, including rest. That’s why I’m on a mission to stop glamorising tiredness. From now on, I plan to get more shut eye and shut up.